From delicate teens to fierce women: Simone Biles’ athleticism and advocacy have changed gymnastics forever

At the 1976 Olympics in Montreal, gymnastics got what it was looking for: an image.

Romania’s Nadia Comăneci was a tiny 14-year-old, leaping on the floor with a pixie-like grace, moving between the bars with lightning fast precision. On her first bar routine, she received a perfect ten: the first ever ten in Olympic Gymnastics.

She would go on to receive seven perfect tens over the course of the 1976 games.

Nadia Comăneci, here in competition at the 1976 Olympics, became the face of gymnastics.

Wikimedia Commons

Comăneci became an icon for the sport, and the image of a young, lithe girl, has endured.

Even through the loss of the perfect ten and the introduction of open scoring – favouring strength and power – women’s gymnastics is still too often dismissed as a sport of frivolity, dominated by children, meek and prepubescent, discouraged from expressing themselves.

Simone Biles – a confident, powerful woman at the peak of her powers in her early 20s – is a change to gymnastics that was inevitable, but is simultaneously one she has come to symbolise.

She is both the greatest gymnast ever, and unlike any gymnast the world ever has seen.

A punishing gymnastics monarch

Comăneci had her run in ‘76 thanks to husband-and-wife coaching team Bela and Márta Károlyi. To understand the pair is to understand the image of the Olympic champion.

Bela was a former boxing champion and member of the national hammer throwing team, later studying gymnastics while at the Romania College of Physical Education.

In his final year at the college he coached the women’s team, which included Márta. After starting their own class in the town where Bela grew up, they were invited to create a national school for gymnastics.

It was when he was training young girls, handpicked for the sport based on their specific body types, he first encountered six-year-old Comăneci.

The Karolyis produced outstanding athletes who seemingly achieved the impossible with focus and ease. In 1981, they defected to the United States, and continued their reign in a new country, building a gym in rural Texas they named Károlyi Ranch. By 1984, Bela had coached new Olympic champions in Mary Lou Retton and Julianne McNamara.

In 1999, Bela was appointed the national team coordinator; and the isolated Károlyi Ranch was designated as the US Women’s National Training Centre. For many years, this gym was a mythologised site of gymnast creation: it would later extensively figure into the sexual abuse trial of former national team doctor Larry Nassar.

The Károlyis had exacting – and often damaging – standards. Gymnasts felt compelled to train and compete with broken bones and other injuries. They divested from the diverse body shapes which once filled the sport for a perpetual state of prepubescence, maintained by punishing overtraining and disordered eating: 1996 Olympic champion Dominique Moceanu has said the athletes were restricted to 900 calories per day.

As hundreds of women would later say in victim impact statements against Nassar, this environment would not only create the “ideal” gymnastic body, but would also create demure girls taught to never talk back. Numerous former athletes – including Romanian team members Rodica Dunca, Emilia Eberle, and Ecaterina Szabo – claim they were subject to regular beatings for making mistakes; and Joan Ryan’s headline-making 1995 book Little Girls in Pretty Boxes contained various allegations of verbal and psychological abuse.

In 2008, Moceanu spoke about the abuse she had faced as a young gymnast – in 2018 she told Deadspin this decision to speak out had ruined her career.

Some of the Karolyis’ athletes have only praised them; others, like Betty Okino in Little Girls in Pretty Boxes, have argued the medals justified the means.

But under their reign from the 1980s until Martha’s retirement in 2016, the US women’s gymnastics team became a superpower.

Competing until they break

Gymnastics is a sport requiring strength and endurance to withstand the G-forces of landings onto the floor, a narrow bar, or thin mat. But it had come to favour bodies possessing neither. As a result, young bodies were pushed to breaking point – with athletes disappearing from the sport in their mid-teens.

Within three years of commencing her senior career, Retton won two American Cups, two American Classics, the all-around competition at the Olympics, and retired.

Within two years, Okino had won two National Championship medals, three at World Championships, contributed to the first American Olympic team victory in 1992, and retired.

In 2016, Laurie Hernandez made her senior debut, winning the City of Jesolo Trophy in Italy, gold for the team at the Pacific Rim Championships, four medals at the US Nationals, and a gold and a silver at the Olympics. She hasn’t competed since.

Countless others followed the same trajectory.

It remains a sport of youth. Olympic gold medallist Jordyn Wieber joined the elite level of the sport at 11, and at 13 she became the second youngest American Cup champion ever; her fellow 2012 gold Olympian, Kyla Ross was 12 when she beat more seasoned future teammates Aly Raisman and McKayla Maroney at the US Classic.

Biles bucked the trend from the beginning. When she was 13, she placed 44th in the pre-elite national championships.

In 2013, when they were both 15, Katelyn Ohashi won gold at the American Cup and Biles won silver. It would be Ohashi’s last elite competition.

It was also the last time anyone would ever beat Biles at the all-around event.

At 19-years-old at the 2016 Rio Olympics, she was already considered old for the sport. She collected five medals – four of them gold.

It was a performance of a lifetime.

A new mould of gymnast

Watching Biles is the opposite to watching Comăneci.

Like the Romanian, she stands under five feet at 142 centimetres – diminutive when compared to many other athletes.

However, Biles has something the 1976 champion did not – explosive strength. She is, as Deadspin describes her, a “power gymnast” who “racked up difficulty on beam using tumbling skills instead of dance elements”.

Comăneci was a consummate performer, but frequently displayed a sense of apprehension, as though liable to snap from a bad landing: a body not built to withstand the force demanded of it.

But Biles competes with the muscle mass and power of male athletes, performing with toned quads, pectorals, and triceps. Her skills defy gravity, going beyond what was thought to be possible in the sport.

Frequently possessing so much energy she bounces out of bounds even after a long pass, she gives a feeling of boundless possibility.

In gymnastics, a new skill becomes named after the first athlete to perform it at an intentional competition. “The Biles” on floor is two flips and half a twist, in a laid-out position, backwards.

At the 2019 World Championships, we will likely have the Biles II: three twists and two flips. Watching footage of this pre-championships, you get the sense she needs to add at least another twist.

But she is not only a revelation in her difficult skills. Her candour – playfulness, jazzy artistry, and irresistible entertainment value – is refreshing, a departure from the strait-laced discipline viewers had become accustomed to, freely incorporating Latin-inspired beats and choreography.

The racism Biles has faced is often disguised as critiques not of her, but of her athleticism and performance. In 2013 David Ciaralli, the Italian Gymnastics Federation’s spokesperson, wrote on Facebook:

the Code of Points is opening chances for coloured people (known to be more powerful) and penalising the typical Eastern European elegance, which, when gymnastics was more artistic and less acrobatic, allowed Russia and Romania to dominate the field.

As recent as this past August, former US National coordinator Valeri Liukin said:

In the Code of Points, difficulty is very valued now. Of course, this suits African Americans. They’re very explosive – look at the NBA, who’s playing and jumping there?

Showing the difficulty

The child prodigies of the sport once telegraphed an air of effortlessness: a confidence and ease that presented tumbling across an inches-wide bar as little more than frivolity in the playground.

But as Biles constantly pushes higher difficulty, she also performs with the gravitas of effort. Despite her ability to turn an exhausting tumbling pass and still be left with energy to burn, she exudes difficulty.

After close to a decade in the training cycle of elite gymnastics – a lengthy tenure in a world of quick rises and falls – her body is likely growing tired from repetitive pounding, regardless of deft pacing.

But there’s another difference to Biles that has become more pronounced with the passing of time: her personality.

Just as the sport was previously a place for girls’ bodies, the athletes were expected be softly spoken with childlike politeness.

But Biles is brave and outspoken.

When Mary Bono was appointed CEO of USA gymnastics in 2018, she lasted three days after Biles publicly called her out for racism against black athletes.

In the wake of the Nassar sexual abuse scandal embroiling peak body USA Gymnastics, Biles has been a rare and consistent voice from a current elite athlete – vocal at competitions and on social media as more failings of accountability and athlete welfare emerge, wisened and hardened with each new revelation.

“You had one job,” she said in August.

You literally had one job and you couldn’t protect us, and it is just really sad because now every time I go to the doctor or training, I get worked on. I don’t want to get worked on, but my body hurts, I’m 22 and at the end of the day that’s my fifth rotation and I have to go to therapy.

In January 2018, as Nassar was being sentenced, Biles tweeted a statement about the trauma she associated with the Károlyi Ranch:

It breaks my heart even more to think that, as I work towards my dream of competing in Tokyo 2020, I will have to continually return to the same training facility where I was abused.

This would not eventuate. Thanks to Biles’ criticism, USA Gymnastics ended its nearly four-decade relationship with the Károlyi Ranch.

The end of an era

Biles has declared the 2020 Olympics will be her last meet.

“I feel like my body’s gone through a lot and it’s kind of just falling apart – not that you can actually tell but I really feel it a lot of the time,” she said in London last year.

If only measuring her career with the hardware she has collected, it would be remarkable – even now, as she goes into the preliminary rounds of the 2019 World Championships in Stuttgart, Germany, she stands with the most all-around titles in the history of the competition – and the most decorated American gymnast of all time.

But the way Biles has shaped the sport with her displays of strength – as an athlete and as an advocate – will arguably be the biggest mark she leaves on the sport.

Biles is a far cry from Comăneci and the diminutive gymnasts of the 70s. But the world of gymnastics is also changing around her.

Internationally, she’s far from the oldest current competitor – in recent years, smaller programs have nurtured more and more experienced athletes through their 20s, 30s, and beyond in the name of retaining top talent.

Among others, at the 2019 Championships Biles will compete against the Netherlands’ Sanne Wevers (aged 28), Germany’s Kim Bui (30), Brazil’s Jade Barbosa (28), and longtime fan-favourite Aliya Mustafina (25) from Russia, who declared “it was easier to give birth than to restore inbars” when recommencing training as a new mother in 2017.

Also competing will be Oksana Chusovitina – 44 years old, in her 17th World Championships, and still one of the best vaulters in the world.

Biles heads into the 2019 World Gymnastics Championships as firm favourite. She is 22, and at the peak of her powers. By this time next year, we will have seen her perform for the final time, undoubtedly having added a new clutch of medals to her collection and leaving more eponymous skills behind.

It’s difficult to predict who will follow in her footsteps, but she’ll leave behind a legacy to be felt for years to come: a trend of women staying in the sport longer, training smarter, and owning their strength as athletes, and as women.

Diversity in race and physique among elite gymnastics is becoming increasingly common. It’s a far cry from decades ago – the US didn’t have Luci Collins, its first African-American Olympic gymnast, until 1980.

For the spectators, the sport is perhaps now less about the artistry of gymnastics, and more about gymnastics as a sport of agility and strength.

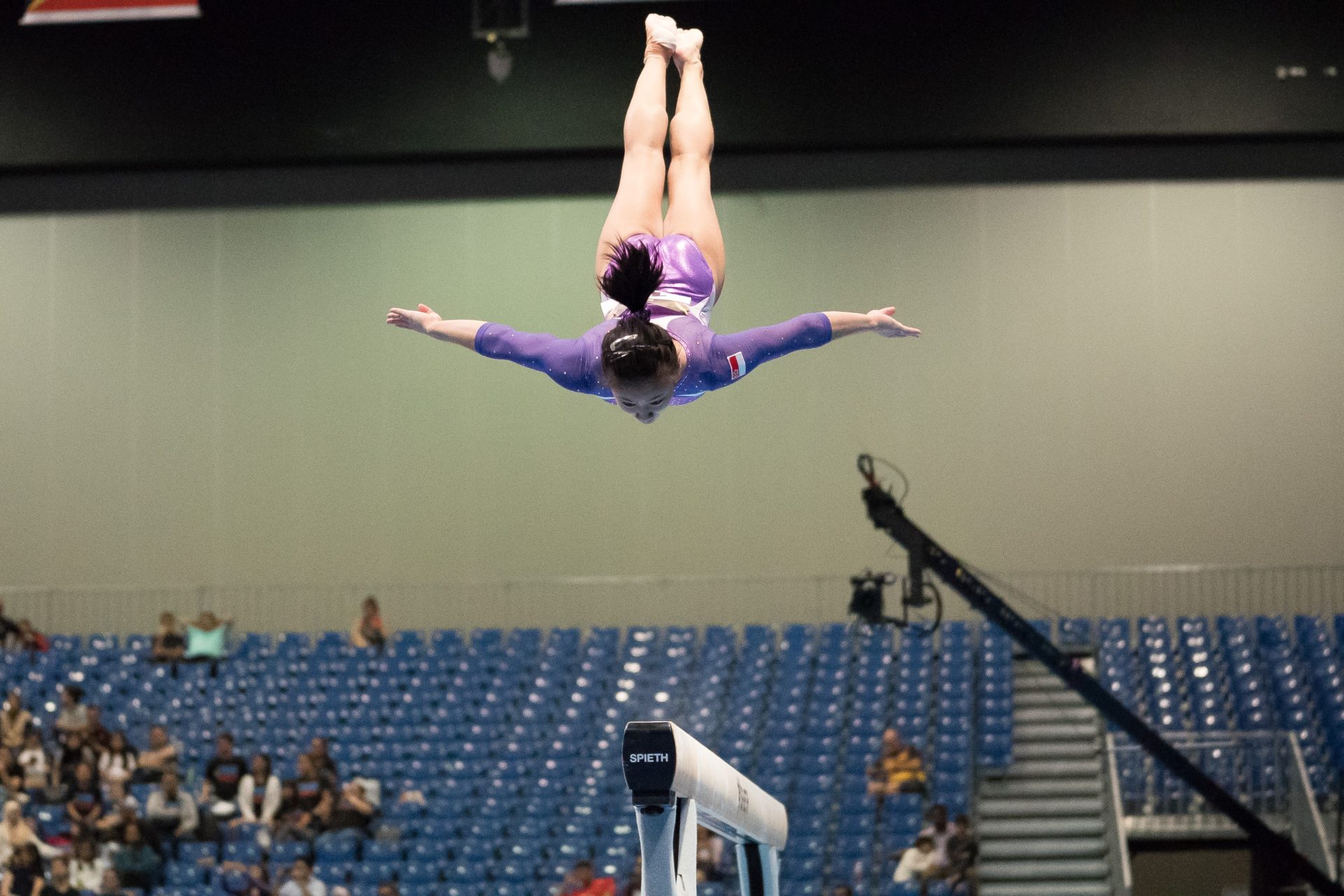

Today, 43 years after Comăneci became the face of gymnastics, the sport has a new image.![]()

Written by Ella Donald, Tutor in Communications and Arts, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.