Humpback whales have been spotted in a Kakadu river. So in a fight with a crocodile, who would win?

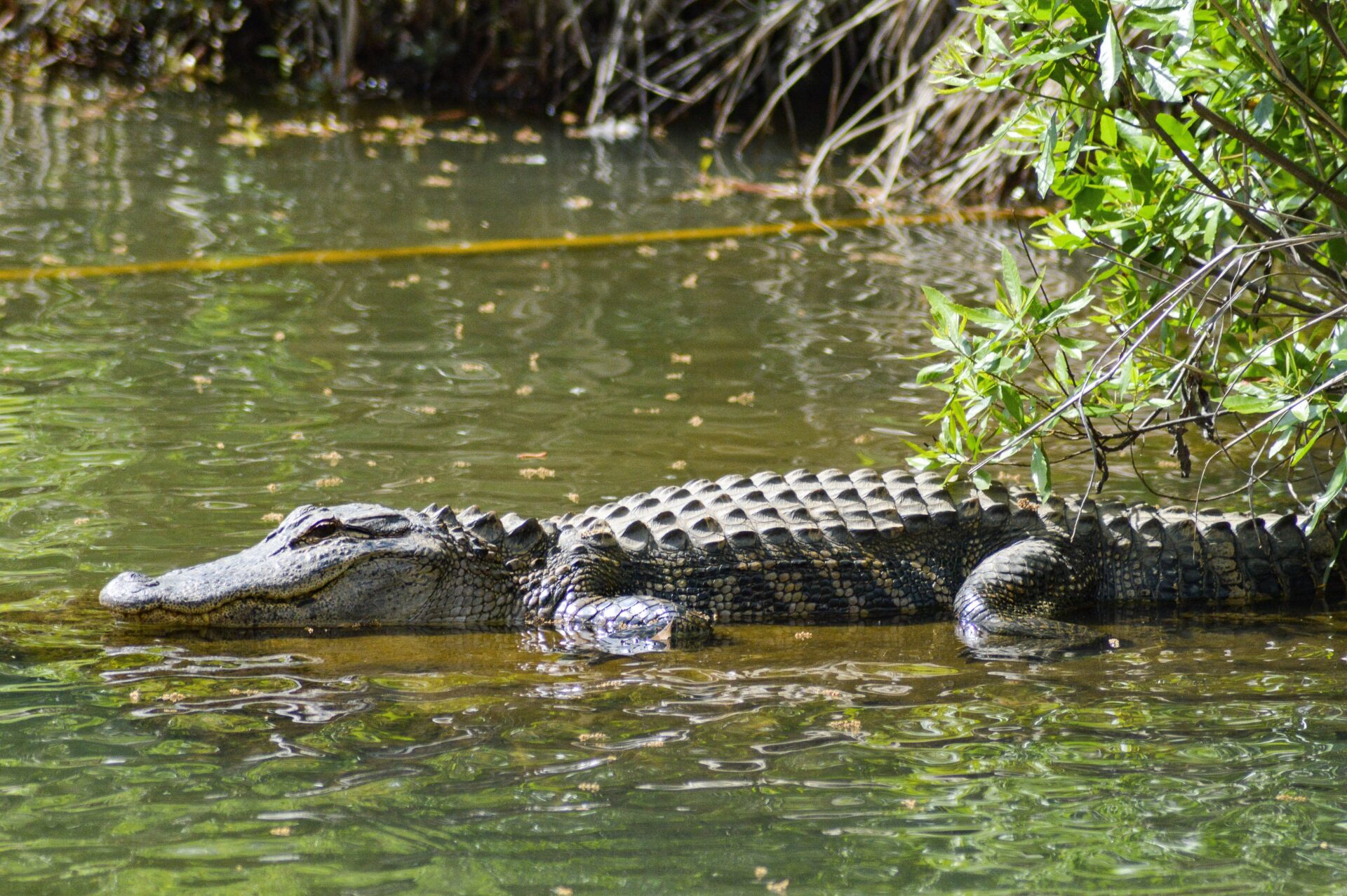

In recent months, three humpback whales were spotted in the East Alligator River in the Northern Territory’s Kakadu National Park. Contrary to its name, the river is full of not alligators but crocodiles. And its shallow waters are no place for a whale the size of a bus.

It was the first time humpback whales had been recorded in the river, and the story made international headlines. In recent days, one whale was spotted near the mouth of the river and scientists are watching it closely.

The whales’ strange detour threw up many questions. How did they end up in the river? What would they eat? Would they get stuck on the muddy river bank?

And of course, there was one big question I was repeatedly asked: in an encounter between a crocodile and a humpback whale, which animal would win?

Dean Lewins/AAP

Scientists double-take

The humpback whales were first spotted in September this year by marine ecologist Jason Fowler and fellow scientists, during a fishing trip. Fowler told the ABC:

I noticed a big spout, a big blow on the horizon and I thought that’s a big dolphin … We were madly arguing with each other about what we were actually seeing. After four hours of raging debate we agreed we were looking at humpback whales in a river.

The whales had swum about 20 kilometres upstream. Fowler photographed the humpback whales’ dorsal fins as evidence, and reported the unusual sighting to authorities and scientists.

Thankfully, two whales returned to sea on their own, leaving just one in need of help. There was concern it might become stranded in the shallow, murky tidal waters. If this happened, it might be attacked by crocodiles – more on this in a minute.

Experts considered a variety of tactics to encourage the whale back out to sea. These included physical barriers such as nets or boats, and playing the sounds of killer whales – known predators of humpback whales.

But none of these these options was needed. After 17 days, the last whale swam back to sea on its own.

The whale that spent two weeks in the river has recently returned and been spotted swimming around the mouth of the river. It appears to have lost weight – most likely the result of migration. It is now being monitored nearby in Van Diemen Gulf.

Questions are now being raised about the health of the animal, and why it has not headed south for Antarctic feedings waters.

Dr Carol Palmer

So why were whales in the river?

The whales are part of Australia’s west coast humpback whale population, which each year travels from cold feeding waters off Antarctica to warm waters in the Kimberley to breed.

There are various theories as to why they swam into the East Alligator River. Humpback whales are extremely curious, and may have entered the river to explore the area.

Alternatively, they may have made a navigation error – also the possible reason behind September’s mass stranding of pilot whales in Tasmania.

And the big question – what about the crocs?

Long-term, a humpback whale’s chances of surviving in the East Alligator River are slim. The lower salinity level may cause them skin problems, and they may become stranded in the shallow waters – unable to move off the muddy bank. Here the animal might die from overheating, or its organs may be crushed by the weight of its body. Or, of course, the whale may be attacked by crocodiles.

In this case, my bet would be on the whale – if it was in relatively good condition and could swim well. Humpback whales are incredible powerful creatures. One flick of their large tail would often be enough to send a crocodile away.

If a croc bit a whale, their teeth would likely penetrate the whale’s skin and thick blubber. But it would take a lot more to do serious harm. Whale skin has been shown to heal after traumatic events, including the case of a humpback whale cut by a boat propeller in Sydney 20 years ago. Dubbed Bladerunner, it survived but still bears deep scars.

Dr Vanessa Pirotta

What next?

The whale sighting continues to fascinate experts. Scientists are hoping to take poo samples from the whale in Van Diemen Gulf, and could also collect whale snot to learn more about its health. However, the best case scenario would be to see the whale swim willingly to offshore waters.

This unusual tale will no doubt go down in Australian whale history. If nothing else, it reminds us of the vulnerability – and resilience – of these marine giants.

Written by Vanessa Pirotta, Wildlife scientist, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.