We need to start vaccinating people in their 20s and 30s, according to the Doherty modelling. An epidemiologist explains why!

Catherine Bennett, Deakin University

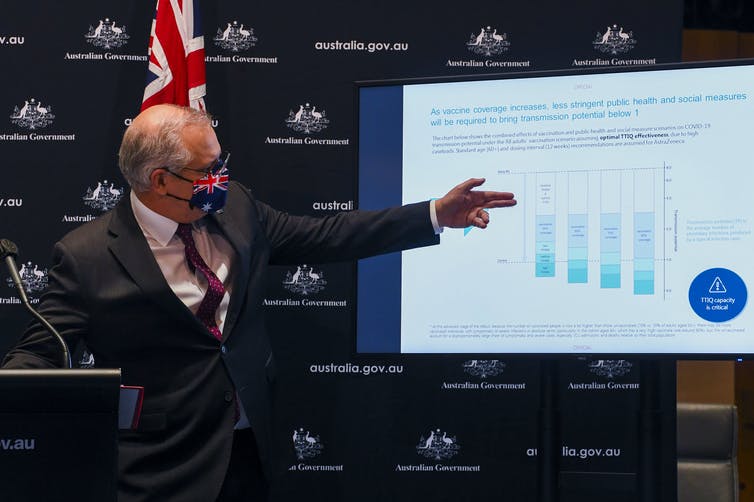

Last week the federal government announced 70% of over-16s would need to be vaccinated for COVID-19 restrictions to be eased.

And this week, Melbourne’s Doherty Institute published the modelling informing this. The Doherty Institute had been asked by national cabinet to model the effects of increasing vaccination rates on Australia’s pathway out of the COVID pandemic.

The collaboration created an impressive assembly of models that allows them to assess the impacts of outbreaks under a range of infection-control scenarios. The model can be adapted to explore easing of specific restrictions, or changed conditions, for example if the dominant variant changes, or our response is more or less effective than anticipated.

They found vaccinating 70% of over-16s would allow for lesser restrictions in the event of an outbreak, and getting to 80% would mean significant easing and likely no lockdowns.

Read more:

Vaccination rate needs to hit 70% to trigger easing of restrictions

The ongoing need for interventions highlights how difficult it is to manage the Delta variant compared to previous strains. Even vaccinating 80% of the population over 16 still requires a level of active control in an outbreak setting, albeit with light restrictions.

The modelling uses Australian data gathered from across the country since August last year. This includes data on “transmission potential”, which is effectively the average number of people one infected person is likely to infect. Under varying levels of public health responses and people’s compliance with restrictions, the modellers were able to estimate this reproduction rate of the virus to understand what it will take to get transmission potential below one, and keep it there, so infections don’t climb beyond manageable levels.

The modelling forecast extends out six months. This is actually a relatively long time horizon given how quickly things change in this pandemic. The parameters start to become unreliable beyond that, and therefore the reliability of forecasts wanes. The modelling is a very well informed best guess, but there are many uncertainties. The value here lies in comparing different scenarios to chart the most strategic course, rather than the specific number of ICU beds or cases predicted.

Read more:

Australia shouldn’t ‘open up’ before we vaccinate at least 80% of the population. Here’s why

The modelling gives us a guide for the level of vaccination coverage we’ll need to control the virus. The 80% mark for those currently eligible delivers a level of protection that promises an escape from our current cycling between lockdowns. It also highlights that time is of the essence — we need to get there before new variants emerge.

If we stay in the current limbo, we’re at risk of community transmission becoming embedded in other states, repeating the New South Wales situation across Australia.

As vaccination rates increase, the need for heavy restrictions decreases, so vaccination is the path out of the limbo we’re in.

Accelerated jabs for younger people after Doherty modelling shows it's vital to vaccinate them quickly https://t.co/i8sfIfhHj8 via @ConversationEDU

— Michelle Grattan (@michellegrattan) August 3, 2021

Why the focus on younger people?

To date, Australia’s rollout has focused on those most at risk of severe outcomes from the disease, including older Australians, protecting them and our health-care systems from overload.

But to reach the vaccination targets in the most effective way, the modelling demonstrates the value in turning our focus now to reducing transmission.

Our highest transmission and case rates occur in 20-39 year olds. This group is the most mobile. They tend to socialise and mix with other people the most and therefore have the most close contacts on average. Many live in shared houses, have young families, and make up a large portion of the workforce, particularly essential workers. The Doherty Institute’s Professor Jodie McVernon said people aged 20-29 in particular were “peak spreaders”.

#ICYMI: @MarylouiseMcla1 says people 20-39 y.o must get priority in the COVID vaccine rollout:

"When you adjust it by the age make-up in the population, they are 70% more likely to catch it… Let's look after them right now. They're our future and our responsibility." #TheDrum pic.twitter.com/fG2Od3mFYB

— ABC The Drum (@ABCthedrum) June 28, 2021

It’s vital we start vaccinating 20-39 year olds, because this approach gives a better bang for our vaccination buck.

Vaccinating this group protects not only them, but the whole population including those who can’t be vaccinated. Vaccinated people are less likely to become infected and, even if they do, less likely to pass it on. The Doherty Institute’s technical report on the modelling indicates the combined effect is a reduction in transmission risk of 86% for AstraZeneca and 93% for Pfizer.

Professor McVernon said vaccinating as many 20-39 year olds as possible could double the protection for over-60s, and protect everyone else, making it the most equitable strategy at this stage of our rollout.

Why weren’t kids included?

The Doherty Institute wasn’t asked to factor in vaccinating those younger than 16, so kids are treated as unvaccinated in the model. Their protection, and the protection of schools from the impact of outbreaks, therefore relies on adults reaching the 80% target, and parents in particular.

The risk here is that if the virus does find its way into schools, it might cause significant outbreaks that quickly spread across schools — like we’re seeing in Queensland at the moment. Stronger public health interventions might still be required to contain an outbreak.

We’ll have to monitor this closely over time, and as COVID vaccine trials in kids continue, to help us weigh up risks and benefits.

This week, ATAGI advised kids aged 12-15 should be prioritised for vaccination if they’re Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, live in a remote community or have underlying medical conditions.

As overall vaccination rates rise, we need to look out for areas with low vaccination coverage. If the virus finds its way in, we may still see a degree of local transmission that requires restrictions. But in these instances, restrictions would be more localised and targeted rather than a whole city or state.

Australia’s Chief Medical Officer, Professor Paul Kelly, said it well in Tuesday’s press conference: we can aim for a “soft landing” where other countries can’t. The modelling tells us when we get to 80% adult vaccination coverage, we can avoid the huge wave of infections we’ve worked so hard to prevent.

Unlike the United Kingdom, where cases peaked again on reopening, or the United States, where cases and hospitalisations are both on the rise, we can leverage our past success in outbreak control and get through this without ever seeing a wave of a truly international proportions.

We asked three paediatricians, a medical ethicist and an epidemiologist if we should vaccinate kids against #COVID19.

4 out of 5 said yes.

Our Deputy Editor, Health + Medicine @Phoebe_Roth explains.https://t.co/IvvLiT2vb9

— The Conversation (@ConversationEDU) August 2, 2021

Catherine Bennett, Chair in Epidemiology, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.