Fear-based politics: what’s the harm?

Blog by Lara Jennings

‘a doctrine which if pushed to its practical consequences would unhinge the fabric of social life, subvert the foundations of religion, order and morality, and substitute for the pure flame of rational freedom, the strange and unhallowed fires of a relentless and licentious anarchy’. – The Australian, 1842

What do you think this quote is talking about? Democracy. Yep. This was how Australian conservatives framed the conversation around democracy at the time. You can practically smell the fear leaping off the page.

Why would someone want to campaign against democracy in such a fear-fuelled way?

Power.

The person who wrote this at the time was a person who had power, and they didn’t want to share it with people that they thought were undeserving (i.e., convicts, women and First Nation Australians).

Throughout history, two distinct types of campaign messages are observable. Those being, fear and hope. Fear is often used to retain power whereas hope is often used to attain it. However, they can both be used for either purpose. As my research guided me, I found that there is real damage caused by campaigns rooted in fear.

How can we be informed voters when political campaigns are designed to trigger us emotionally, with strategically employed visuals and music? Facts matter, but they are clearly no match for a political campaign fuelled by fear and/or hope, as can be seen throughout the political campaign history books.

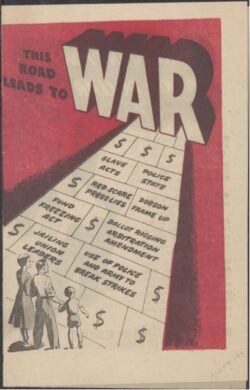

Image from The National Library of Australia Federal Election Ephemera Collection #2247771

The image above is an example of campaign material from the Labor camp that was designed to scare voters into thinking that the Liberal Party was going to lead the country to war (circa late 1940s).

Labor, with Keating at the helm, again used fear tactics to oppose John Hewson’s Tax Reforms in the 1990s, which were centred around the introduction of the GST. It worked.

Conservative parties have also done more than their fair share of scare campaigns throughout the years. Interestingly, it was a lot easier to find fear-based election materials throughout history from conservative parties, than it was to find ones from progressive parties (fascinating tidbit… wonder why that is?).

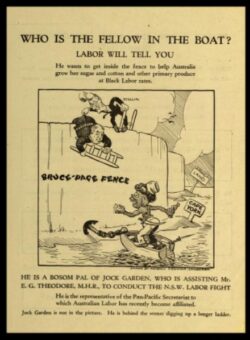

The image below was circulated during the late 1920s federal election campaign, by the conservative Nationalist-Country Coalition. This graphic was designed to elicit fear of foreign farmers coming to take away Australian agricultural income sources in the sugar and cotton industries. This is unfortunately a common theme in our nation’s political campaigns.

Image from The National Library of Australia Federal Election Ephemera Collection #2247771

Lachlan Harris, the former media advisor to Kevin Rudd, spoke about the use of fear in politics, saying: “people use fear in politics because it works. And it’s the simplest and easiest to communicate.”

The general fear playbook has the same process no matter where it is played out in the world.

- Create an enemy, someone different, usually an outsider who is scary and bad (think Big Bad Wolf vibes).

- Tell the public that if they let the opposing party into power, then this enemy will attack/destroy lives/take away what is theirs.

A key part to Putin’s strategy for his invasion of Ukraine, was to convince the people of Russia that Ukraine was being run by neo-nazis, and that they needed to free the Ukrainian people from the rule of people with right-wing extremist views. The Kremlin is working hard to convince Russia and the world that they need to “de-nazify” Ukraine.

We have already seen the fear strategy used domestically in the lead up to this year’s election, where Scott Morrison referred to a Labor MP as a ‘Manchurian candidate’ during parliament in February. During an interview on the ABC in response to the comments of Morrison, ASIO Director General Mike Burgess clarified that there were risks with both parties and that using national security as a policy campaign strategy was not helpful.

One of the reasons why fear campaigns aren’t helpful, is because they demonise people. The damage of this demonisation can last for decades in the form of racist bias. Our foreign policy is created around the idea that people from other countries can’t be trusted, and that we must protect Australians from outsiders. The way people think about refugees today is still heavily influenced by the fear- campaign run by John Howard in 2001. The now infamous line of, “we will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come”, as spoken by Howard in his election policy speech in February 2013. Decades later, we still have mandatory detention for people who don’t have a visa and are seeking refuge from war- torn countries.

If a fear-based campaign is not helpful as a defence strategy, why do politicians still use it? The simple answer is because it works ridiculously well in domestic political campaigns. When a campaign triggers an emotional response, it overrides rational thinking.

And when it works, politicians are rewarded with power.