A new discovery shows major flowering plants are 150 million years older than previously thought

Byron Lamont, Curtin University

A major group of flowering plants that are still around today, emerged 150 million years earlier than previously thought, according to a new study published today in Trends in Plant Science. This means flowering plants were around some 50 million years before the dinosaurs.

The plants in question are known as the buckthorn family or Rhamnaceae, a group of trees, shrubs and vines found worldwide. The finding comes from subjecting data on 100-million-year old flowers to powerful molecular clock techniques – as a result, we now know Rhamnaceae arose more than 250 million years ago.

A widespread family

Today, the buckthorn family of shrubs is widespread throughout Africa, Australia, North and South America, Asia and Europe. The important fruit jujube or Chinese date belongs to the Rhamnaceae; other species are used in ornamental horticulture, as sources of medicine, timber and dyes, and to add nitrogen to the soil.

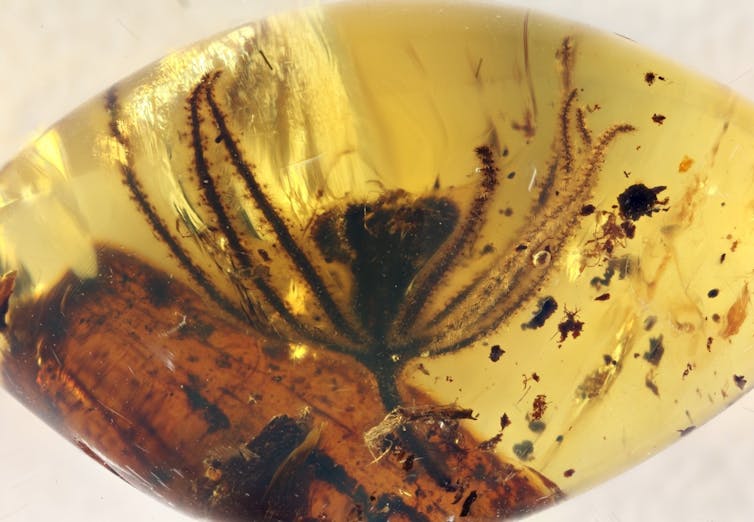

Flowering shoots of the shrub Phylica, now confined to South Africa, have recently been found in amber from Myanmar that is more than 100 million years old.

Together with Tianhua He, a molecular geneticist at Murdoch University, we combined skills to show these new fossils of Phylica could be used to trace the Rhamnaceae family (to which Phylica belongs) back to its origin almost 260 million years ago.

We did this by comparing the DNA of living plants of Phylica against the rate of DNA change over the past 120 million years, to set the molecular clock for the rest of the family.

Prof Shuo Wang/Shi et al. 2022, Author provided

Older than we could have imagined

It was previously believed that Phylica evolved about 20 million years ago and Rhamnaceae about 100 million years ago, so these new dates are much older than botanists could possibly have imagined. Since Rhamnaceae is not even considered an old member of the flowering plants, this means flowering plants arose more than 300 million years ago – some 50 million years before the rise of the dinosaurs.

But how did Phylica get from the Cape of South Africa to Myanmar? Our data on the history of the plant’s evolution show the most likely path is that Phylica migrated to Madagascar, then to the far north of India (most of which is under the Himalayas now), all of which were joined 120 million years ago.

India then separated and drifted north until it collided with Asia. The far northeast section, known as the Burma tectonic plate, became Myanmar about 60 million years ago. Sap, possibly released by fire-injured conifers, flowed over the Phylica flowers and preserved them intact as amber while India was still attached to Madagascar.

Forged in fires

In fact, the vegetation in which Rhamnaceae evolved was probably subjected to regular fires. The first clue was the charcoal researchers have found together with the Phylica fossils in the amber.

The second is that today, almost all living species in the Phylica subfamily have hard seeds that require fire to stimulate them to germinate.

I assessed the fire-related traits of as many living species as possible, then He traced them onto the evolutionary tree he had created, using a technique called ancestral trait assignment. This showed there was a strong possibility the earliest Rhamnaceae ancestor was fire-prone and produced hard seeds.

We have extensively studied the evolutionary fire history of banksias, which go back 65 million years, along with proteas, pines, wire rushes and the kangaroo paw family.

Our new results make the buckthorn family of plants by far the oldest to show fire-related traits of all the plants we have studied over the past 12 years.![]()

Byron Lamont, Distinguished Professor Emeritus in Plant Ecology, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.