From Chaucer to chocolates: how Valentine’s Day gifts have changed over the centuries

Clare Davidson, Australian Catholic University

For Valentine’s Day, some couples only roll their eyes at each other in mutual cynicism. The capitalisation of love in the modern world can certainly seem banal.

But Valentine’s Day gifts are hardly a contemporary invention. People have been celebrating the day and gifting love tokens for hundreds of years.

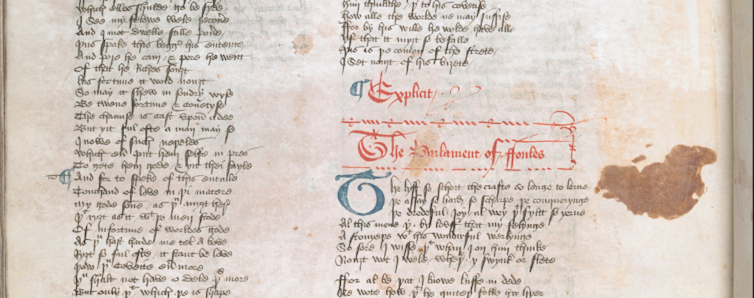

We should first turn to Geoffrey Chaucer, the 14th-century poet, civil servant and keen European traveller. Chaucer’s poem from the 1380s, The Parliament of Fowls, is held to be the first reference to February 14 as a day about love.

This day was already a feast day of several mysterious early Roman martyred Saint Valentines, but Chaucer described it as a day for people to choose their lovers. He knew that was easier said than done.

The narrator of the poem is unsuccessful in love, despairing that life is short compared with how long it takes to learn to love well. He falls asleep and dreams of a garden in which all the different birds of the world have gathered.

Nature explains to the assembled flocks that, like every year on St Valentine’s Day, they have come to pick their partners in accordance with her rules. But this process causes confusion and debate: the birds can’t agree what it means to follow her rules because they all value different things in their partners.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Legal and emotional significance

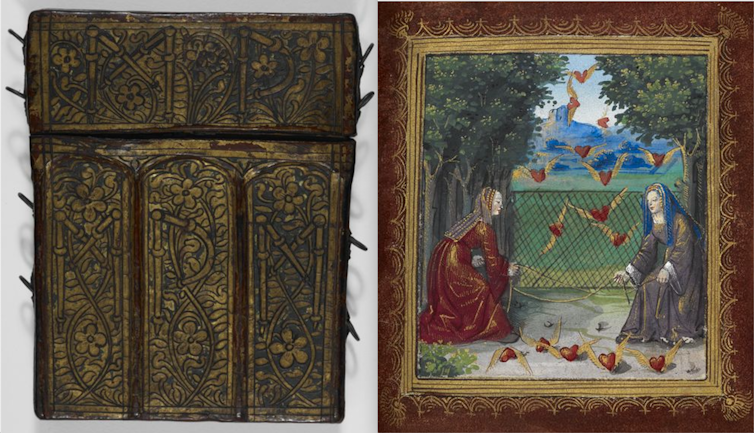

Like today, in Chaucer’s time gift-giving could be highly ritualised and symbolise intention and commitment. In Old and Middle English, a “wed” was any sort of token pledged to guarantee a promise. It was not until the 13th century that a “wedding” came to mean a nuptial ceremony.

The same period saw marriage transform into a Christianised and unbreakable commitment (a sacrament of the Church). New conventions of love developed in songs, stories and other types of art.

These conventions influenced broader cultural ideas of emotion: love letters were written, grand acts of service were celebrated, and tokens of love were given.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Rings, brooches, girdles (belts), gloves, gauntlets (sleeves), kerchiefs or other personalised textiles, combs, mirrors, purses, boxes, vessels and pictures – and even fish – are just some examples of romantic gifts recorded from the late middle ages.

Victoria and Albert Museum

In stories, gifts could be imbued with magical powers. In the 13th century, in a history of the world, Rudolf von Ems recorded how Moses, when obliged to return home and leave his first wife Tharbis, an Ethiopian princess, had two rings made.

The one he gave her would cause Tharbis to forget him. He always wore its pair which kept her memory forever fresh in his mind.

J. Paul Getty Museum

Outside of stories, gifts could have legal significance: wedding rings, important from the 13th century, could prove that a marriage had occurred by evidencing the intention and consent of the giver and recipient.

The art of loving

Like Chaucer, 20th-century German psychologist Erich Fromm thought people could learn the art of loving. Fromm thought love was an act of giving not just material things, but one’s joy, interest, understanding, knowledge, humour and sadness.

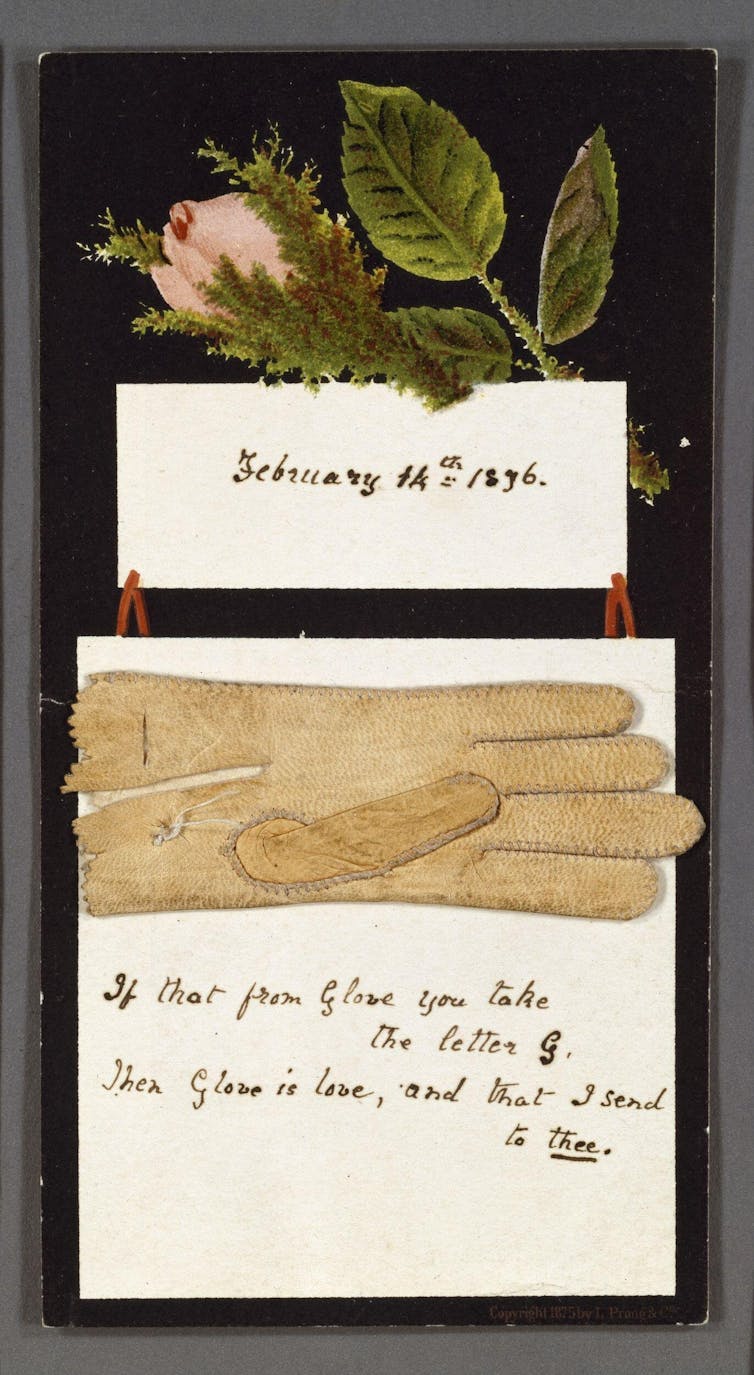

While these gifts might take some time and practice, there are more straightforward ideas from history. Manufactured cards have dominated since the industrial revolution, taking their place alongside other now traditional presents such as flowers, jewellery, intimate apparel and consumables (now more often chocolates than fish). All can be personalised for that intimate touch.

Bequeathed by Guy Tristram Little, Victoria and Albert Museum

There have, of course, been weirder examples of love gifts, such as Angelina Jolie and Billy Bob Thornton exchanging necklaces with silver pendants smeared with each other’s blood.

Artist Dora Maar was so upset when her notoriously bad lover Pablo Picasso complained about having to trade a painting for a ruby ring she immediately threw the ring in the Seine. Picasso soon replaced it with another, this one featuring Maar’s portrait.

A good love token can long outlast the feelings that prompt its giving: a flower pressed in a book, a trinket at the bottom of a box, a fading heartfelt card or a bittersweet song that jolts you back to an earlier time. In this way, the meaning of gifts can change as they become reminders that all things pass.![]()

Clare Davidson, Research Associate, Gender and Women’s History Research Centre, Australian Catholic University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.