Our study found new teachers perform just as well in the classroom as their more experienced colleagues

Jenny Gore, University of Newcastle

The past four decades have seen an endless stream of reviews into teacher education. Australia has clocked up more than 100 since 1979. This comes amid constant concerns teachers are not adequately prepared for the classroom.

Our latest research, published in the Australian Education Researcher, provides a powerful counternarrative to concerns about teacher education and early-career teachers.

We analysed data from two major studies over the past decade and found it did not matter if teachers had less than one year of teaching experience or had spent 25 years in the classroom – they delivered the same quality of teaching.

These results indicate teaching degrees are preparing new teachers to deliver quality teaching and have a positive impact in their classrooms right away.

Recent reviews into teacher education

The most recent review into teacher education was finalised in February 2022. Led by former federal education department secretary Lisa Paul, the review found an “ambitious reform agenda” was needed to attract “high quality” students and make sure teacher education was “evidence-based and practical”.

Sydney University vice-chancellor Mark Scott (who also chairs The Conversation’s board) is now leading another expert panel, partly in response to Paul’s review and partly due to concerns about teacher shortages. It is looking at how to “strengthen” teacher education. It is also looking at developing a “quality measure” for teaching degrees and whether funding for universities should be tied to quality.

In among this, we have already seen an emphasis on attracting the “best and brightest” into teaching degrees and increasing requirements to graduate. To enter a classroom, teachers now need to have passed extra literacy and numeracy tests on top of their degrees.

The underlying assumption in all this government messaging and accompanying media commentary is that failings in education are those of teachers and teacher educators (the academics who teach teachers).

Our research

Our research used direct observation of 990 entire lessons to investigate the relationship between years of teaching experience and the quality of teaching.

We analysed the teaching of 512 Year 3 and 4 teachers from 260 New South Wales public schools in separate studies conducted over 2014-15 and 2019-21.

The schools involved in the study were representative of schools across Australia, and the lessons observed included a range of subjects, with the majority in English and mathematics. Most of the teachers observed had between one and 15 years of experience, although almost a quarter of the observations were of lessons taught by teachers with 16 years’ experience or more.

How we assess quality teaching

We used the Quality Teaching Model as the basis for the observations. The model was developed by education academic James Ladwig and me for the NSW Department of Education in 2003. It has been the department’s framework for high-quality teaching since.

It is based on research into the types of teaching practice that make a difference to student learning and centres on three dimensions:

- “intellectual quality” – developing deep understanding of important knowledge

- “a quality learning environment” – ensuring positive classrooms that boost student learning, and

- “significance” – connecting learning to students’ lives and the wider world.

Under these three dimensions are 18 elements of teaching practice that enable detailed analysis of lesson quality. Researchers coded the lessons they observed, with more than one researcher coding many of the lessons to ensure a high level of reliability.

Our findings

We found no statistically significant differences in average teaching quality across the years of experience categories.

Even when we broke down the experience categories in different ways to test for accuracy, we continued to find that years of experience did not equate to differences in the quality of teaching delivered.

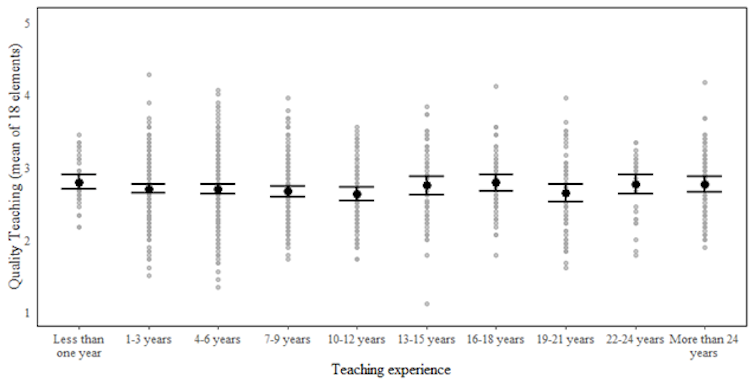

On the graph below, each dot represents the average Quality Teaching score of an observed lesson. These have been grouped in a line based on how experienced a teacher is.

The average lesson quality in each experience category is represented by the large black dot and the horizontal lines represent the margin of error. The average Quality Teaching score across all the experience categories falls within the same margin of error range illustrating no statistically significant difference.

Author provided

Why does experience appear to make no difference?

Teaching quality is consistently described as the most important in-school factor affecting student outcomes.

Our finding that newly graduated teachers deliver teaching of a similar quality to that of their more experienced peers is surprising and somewhat counterintuitive. There are at least two possible explanations for this result.

First, the result suggests graduate teachers are entering the profession “classroom ready” because initial teacher education programs are performing far better than is typically assumed in policy and the media.

That is not to say improvements in teaching degrees aren’t possible or warranted, or that graduate teachers don’t face difficulties. We know attrition among teachers in their first five years is high and is a major contributor to teacher shortages.

Second, on-the-job experience is insufficient on its own to raise teaching quality. While experienced teachers make many valuable contributions through leadership and mentoring, it could be that much of the professional development they do over the course of their careers makes little difference to the quality of their teaching practice.

Teachers need professional development that builds knowledge, motivates them, develops their teaching techniques and helps them make ongoing changes in their classroom practice. It should be backed by rigorous evidence of a positive impact on teaching quality and student outcomes.

Teachers and teaching

Part of the problem in debates about schools and education is the relentless use of “teacher quality” as a proxy for understanding “teaching quality”. This focuses on the person rather than the practice.

This discourse sees teachers blamed for student performance on NAPLAN and PISA tests, rather than taking into account the systems and conditions in which they work.

While teaching quality might be the greatest in school factor affecting student outcomes, it’s hardly the greatest factor overall. As Education Minister Jason Clare said last month:

I don’t want us to be a country where your chances in life depend on who your parents are or where you live or the colour of your skin.

We know disadvantage plays a significant role in educational outcomes. University education departments are an easy target for both governments and media.

Blaming them means governments do not have to try and rectify the larger societal and systemic problems at play.![]()

Jenny Gore, Laureate Professor of Education, Director Teachers and Teaching Research Centre, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.