Anxious dogs have different brains to normal dogs, brain scan study reveals

Melissa Starling, University of Sydney

Dog ownership is a lot of furry companionship, tail wags and chasing balls, and ample unconditional love. However, some dog owners are also managing canine pals struggling with mental illness.

A newly published study in PLOS ONE has examined the brain scans of anxious and non-anxious dogs, and correlated them with behaviour. The research team at Ghent University, Belgium, found that our anxious dog friends not only have measurable differences in their brains linked to their anxiety, but these differences are similar to those found in humans with anxiety disorders as well.

Anxious friends

Anxiety disorders in humans are varied and can be categorised into several main types. Overall, they represent high levels of fear, emotional sensitivity and negative expectations. These disorders can be difficult to live with and sometimes difficult to treat, in part due to how varied and complex anxiety is.

Researching anxiety in animals can help us to understand what drives it, and to improve treatment for both humans and animals. The new study sought to investigate possible pathways in the brain that are associated with anxiety in dogs. Understanding this could both improve treatment for anxiety in veterinary medicine, and reveal similarities with what we know of human anxiety.

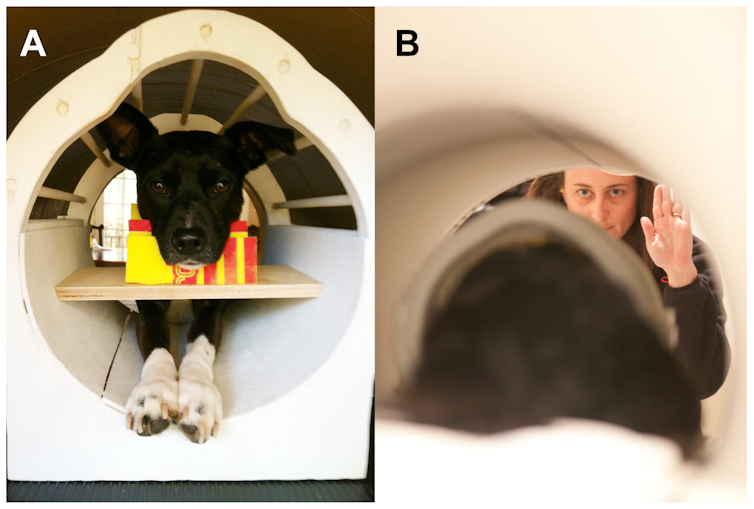

Dogs with and without anxiety were recruited for functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans of their brains. Dogs have been involved in awake fMRI studies before, but for this one, with dogs that might get easily stressed out, the dogs were under general anaesthesia.

Owners of the dogs also filled out surveys on their pets’ behaviour. The researchers performed data analysis and modelling of brain function, focusing on regions of the brain likely to show differences related to anxiety. Based on previous research on animal and human anxiety, the team dubbed these brain regions the “anxiety circuit”.

They then analysed whether there were differences between the brain function of anxious and non-anxious dogs, and if those differences actually related to anxious behaviours.

Berns et al., 2012

Different brains

The researchers found there were indeed significant differences between anxious and non-anxious dogs. The main differences were in the communication pathways and connection strength within the “anxiety circuit”. These differences were linked with higher scores for particular behaviours in the surveys as well.

For example, anxious dogs had amygdalas (an area of the brain associated with the processing of fear) that were particularly efficient, suggesting a lot of experience with fear. (This is similar to findings from human studies.) Indeed, in the behaviour surveys, owners of anxious dogs noted increased fear of unfamiliar people and dogs.

The researchers also found less efficient connections in anxious dogs between two regions of the brain important for learning and information processing. This may help explain why the owners of the anxious dogs in the study reported lower trainability for their dog.

A difficult time

Brains are exquisitely complex biological computers, and our understanding of them is far from comprehensive. As such, this study should be interpreted cautiously.

The sample size was not large or varied enough to represent the entire dog population, and the way the dogs were raised, housed, and cared for could have had an effect. Furthermore, they were not awake during the scans, and that also may have influenced some of the results.

However, the study does show strong evidence for measurable differences in the way anxious dog brains are wired, compared to non-anxious dogs. This research can’t tell us whether changes in the brain caused the anxiety or the other way around, but anxiety in dogs is certainly real.

It’s in the interests of our anxious best friends that we appreciate they may be affected by a brain that processes everything around them differently to “normal” dogs. This may make it difficult for them to learn to change their behaviour, and they may be excessively fearful or easily aroused.

Thankfully, these symptoms can be treated with medication. Research like this could lead to more finessed use of medication in anxious dogs, so they can live happier and better adjusted lives.

If you have a dog you think might be anxious, you should speak to a veterinarian with special training in behaviour.![]()

Melissa Starling, Postdoctoral researcher, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.